எழில் இனப் பெருக்கம்

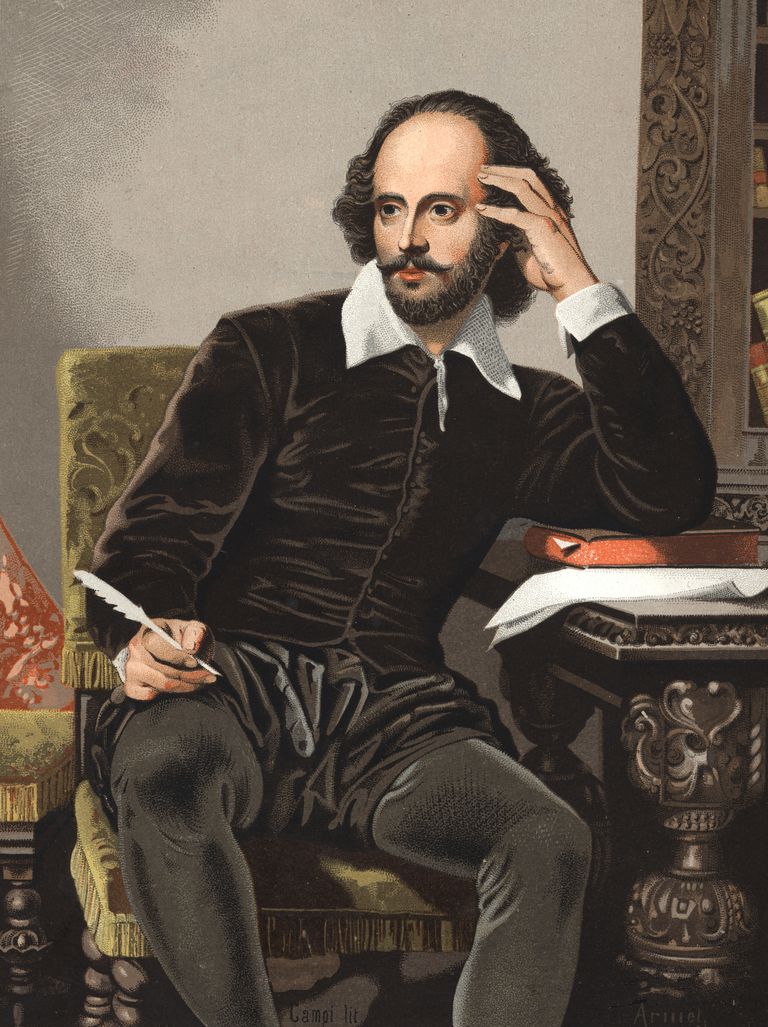

முன்னுரை: நாடக மேதை வில்லியம் ஷேக்ஸ்பியர் 154 ஈரேழ்வரிப் பாக்கள் எழுதியிருப்பதாகத் தெரிறது. 1609 ஆம் ஆண்டிலே ஷேக்ஸ்பியரின் இலக்கிய மேன்மை அவரது நாடகங்கள் அரங்கேறிய குலோப் தியேட்டர் (Globe Theatre) மூலம் தெளிவாகி விட்டது. அந்த ஆண்டில்தான் அவரது ஈரேழ்வரிப் பாக்கள் தொகுப்பும் முதன்முதலில் வெளியிடப் பட்டது.

ஷேக்ஸ்பியரின் ஈரேழ்வரிப் பாக்கள் ஆங்கில மொழியில் வடிக்கப் பட்டுள்ள காதற் கவிதைகள். அவை வாலிபக் காதலருக்கு மட்டுமின்றி அனுபவம் பெற்ற முதிய காதலருக்கும் எழுதியுள்ள ஷேக்ஸ்பியரின் ஒரு முதன்மைப் படைப்பாகும். அந்தக் காலத்தில் ஈரேழ்வரிப் பாக்கள் பளிங்கு மனமுள்ள அழகிய பெண்டிர்களை முன்வைத்து எழுதுவது ஒரு நளின நாகரிகமாகக் கருதப் பட்டது. ஷேக்ஸ்பியரின் முதல் 17 பாக்கள் அவரது கவர்ச்சித் தோற்ற முடைய நண்பனைத் திருமணம் செய்ய வேண்டித் தூண்டப் பட்டவை. ஆனால் அந்தக் கவர்ச்சி நண்பன் தனக்குப் பொறாமை உண்டாக்க வேறொரு கவிஞருடன் தொடர்பு கொள்கிறான் என்று ஷேக்ஸ்பியரே மனம் கொதிக்கிறார். எழில் நண்பனை ஷேக்ஸ்பியரின் ஆசை நாயகியே மோகித்து மயக்கி விட்டதாகவும் எண்ணி வருந்துகிறார்.. ஆனால் அந்த ஆசை நாயகி பளிங்கு மனம் படைத்தவள் இல்லை. அவளை ஷேக்ஸ்பியர் தன் 137 ஆம் ஈரேழ்வரிப் பாவில் “மனிதர் யாவரும் சவாரி செய்யும் ஒரு வளைகுடா” (The Bay where all men ride) – என்று எள்ளி இகழ்கிறார்.

அவரது 20 ஆவது ஈரேழ்வரிப் பாவின் மூலம் அந்தக் காதலர்கள் தமது ஐக்கிய சந்திப்பில் பாலுறவு கொள்ளவில்லை என்பதும் தெரிய வருகிறது. ஐயமின்றி ஷேக்ஸ்பியரின் ஈரேழு வரிப்பாக்கள் அக்கால மாதரின் கொடூரத்தனத்தையும், வஞ்சக உறவுகளைப் பற்றியும் உணர்ச்சி வசமோடு சில சமயத்தில் அவரது உடலுறவைப் பற்றியும் குறிப்பிடுகின்றன ! ஷேக்ஸ்பியரின் நாடக அரங்கேற்றமும் அவரது கவிதா மேன்மையாகவே எடுத்துக் கொள்ளப் படுகிறது. அவரது முதல் 126 ஈரேழ்வரிப் பாக்கள் தனது நண்பன் ஒருவனை முன்னிலைப் படுத்தி எழுதப் பட்டவையே. மீதியுள்ள 28 பாக்கள் ஏதோ ஒரு கருப்பு மாதை வைத்து எழுதப் பட்டதாக அறியப் படுகிறது. இறுதிப் பாக்கள் முக்கோண உறவுக் காதலர் பற்றிக் கூறுகின்றன என்பதை 144 ஆவது பாவின் மூலம் அறிகிறோம். ஷேக்ஸ்பியரின் ஈரேழ்வரிப் பாக்களில் சிறப்பாகக் கருதப்படுபவை : 18, 29, 116, 126 & 130 எண் கவிதைகள்.ஷேக்ஸ்பியரின் ஈரேழ்வரிப் பாக்கள் எந்த ஒரு சீரிய ஒழுங்கிலோ, நிகழ்ச்சிக் கோர்ப்பிலோ தொடர்ச்சி யாக எழுதப் பட்டவை அல்ல. எந்தக் கால இணைப்பை ஓட்டியும் இல்லாமல் இங்கொன்றும், அங்கொன்றுமாக அவை படைக்கப் பட்டவை. நிகழ்ந்த சிறு சம்பவங்கள் கூட ஆழமின்றிப் பொதுவாகத் தான் விளக்கப் படுகின்றன. காட்டும் அரங்க மேடையும் குறிப்பிட்டதாக இல்லை. ஷேக்ஸ்பியர் தனது நண்பனைப் பற்றியும் அவனது காதலியின் உறவைப் பற்றியும் எழுதிய பாக்களே நான் தமிழாக்கப் போகும் முதல் 17 ஈரேழ்வரிப் பாக்கள். இவற்றின் ஊடே மட்டும் ஏதோ ஒருவிதச் சங்கிலித் தொடர்பு இருப்பதாகக் காணப் படுகிறது. ஷேக்ஸ்பியர் தனது பாக்களில் செல்வீக நண்பனைத் திருமணம் புரியச் சொல்லியும் அவனது அழகிய சந்ததியைப் பெருக்கி வாழ்வில் எழிலை நிரந்தரமாக்க வேண்டுமென்றும் வற்புறுத்துகிறார். ஆதலால் ஷேக்ஸ்பியரின் முதல் 17 ஈரேழ்வரிப் பாக்கள் “இனப் பெருக்கு வரிப் பாக்கள்” (Procreation Snnets) என்று பெயர் அளிக்கப் படுகின்றன.

உனக்குப் பகை நீதான் !

(ஈரேழ் வரிப்பா – 1)

நளினப் பிறவிகள் மூலம் நாம்

விழைவது எழில் இனப் பெருக்கம் !

அழகு ரோஜா ஒருபோதும் அழியாது

காலப் போக்கில் பெறுபவர் மரிப்பினும் !

வாலிபச் சந்ததி விருத்தி செய்து

நிலைத்திடும் நினைவுகள் பற்பல ஜென்மம் !

நீ அதைக் கட்டுப்பாடு செய்; ஆயினும்

நின் தீபத் தீயிக்கு எண்ணை

நீயே சுயமாய் நிரப்புவது !

நேர்ந்திடும் பஞ்சம் அதனால் சந்ததிக்கு

பேரளவு செழிப்புள்ள போதும் !

உனக்கு நீ பகைவனாய் உள்ளாய் !

இனிய சுயநலம் மிகவும் கொடியது !

ஒளிமிகும் புது உலக ஆபரணம் நீ !

ஒற்றைத் தூதுவன் ! உன்

வசந்த வனப்பு மங்கிப் போவது !

உனது மொட்டுக்குள் புதையும்

உன் சுய திருப்தி எல்லாம் !

சேமிப்பை வீணாக் காமல்

இன விருத்தியைத் தொடர் !

பரிவு கொள் இந்தப் புவி மீது

பெருந்தீனி மானிடன் இன்றேல்

உண்பான் புதை குழிபோல்

உலகுக் குரிய வற்றை !

(Shakespeare’s Sonnets : 1)

From fairest creatures we desire increase,

That thereby beauty’s rose might never die,

But as the riper should by time decease,

His tender heir might bear his memory:

But thou, contracted to thine own bright eyes,

Feed’st thy light’st flame with self-substantial fuel,

Making a famine where abundance lies,

Thyself thy foe, to thy sweet self too cruel.

Thou that art now the world’s fresh ornament

And only herald to the gaudy spring,

Within thine own bud buriest thy content

And, tender churl, makest waste in niggarding.

Pity the world, or else this glutton be,

To eat the world’s due, by the grave and thee.

Sonnet 1 Summary

As the opening sonnet of the sequence, this one obviously has especial importance. It appears to look both before and after, into the future and the past. It sets the tone for the following group of so called ‘procreation’ sonnets 1-17. In addition, many of the compelling ideas of the later sonnets are first sketched out here – the youth’s beauty, his vulnerability in the face of time’s cruel processes, his potential for harm, to the world, and to himself, (perhaps also to his lovers), nature’s beauty, which is dull in comparison to his, the threat of disease and cankers, the folly of being miserly, the need to see the world in a larger sense than through one’s own restricted vision.

‘Fair youth, be not churlish, be not self-centred, but go forth and fill the world with images of yourself, with heirs to replace you. Because of your beauty you owe the world a recompense, which now you are devouring as if you were an enemy to yourself. Take pity on the world, and do not, in utter selfish miserliness, allow yourself to become a perverted and self destructive object who eats up his own posterity’.

காலத்தை வீணாக்காதே !

(ஈரேழு வரிப்பா – 2)

நாற்ப தாண்டு குளிர்காலத் தடங்கள் உன்

புருவத்தைச் சூழும் போது அகண்ட கீறல்கள்

அழகு மேனியில் தோண்டப் படும் !

இளமைப் பீடு உடை இன்று மினுப்பது

கிழிந்த அணியாய்ச் சிறு மதிப் படையும் !

ஒப்பனை உனக்கு ஒளிந்துள தெங்கே ?

காமக்களி நாட்களின் சேமிப்பு எங்கே ?

குழிந்த உன் விழிகளுக்குள் தெரியும்.

அவமானம் விழுங்கும் நேர்மை உணர்வை

புகழ்ச்சி அளிக்காது எந்த ஊதியமும் !

இதற்கு மேல் எத்தகைத் தகுதி பெறும்

எழில் மேனியின் பயன் பாடு ?

இந்த மகவு எனக் குரியதா வென்னும்

வினாவுக்கு விடை தர முடிந்தால்

எடை போடு எனது வாழ்வை !

எத்தனை மாதர்கள் எனக்கெனக் கணக்கிடு

முதியவன் என்று நியாயம் அளித்திடு

அழகுக்குச் சோதனை ! எழிலுக்கு வாரிசு !

புதிதாய் இவை படைப் பானவை !

உன்னுருவில் உதித்த மதலை உனக்கு

முதிய வயதுச் சின்னம் ! கணப்பு

உதிரம் மீண்டும் ஓடும் குளிர்காலம் !

(Shakespeare’s Sonnets : 2)

When forty winters shall besiege thy brow,

And dig deep trenches in thy beauty’s field,

Thy youth’s proud livery, so gazed on now,

Will be a tatter’d weed, of small worth held:

Then being ask’d where all thy beauty lies,

Where all the treasure of thy lusty days,

To say, within thine own deep-sunken eyes,

Were an all-eating shame and thriftless praise.

How much more praise deserved thy beauty’s use,

If thou couldst answer ‘This fair child of mine

Shall sum my count and make my old excuse,’

Proving his beauty by succession thine!

This were to be new made when thou art old,

And see thy blood warm when thou feel’st it cold.

Sonnet 2 Summary

The poet looks ahead to the time when the youth will have aged, and uses this as an argument to urge him to waste no time, and to have a child who will replicate his father and preserve his beauty. The imagery of ageing used is that of siege warfare, forty winters being the besieging army, which digs trenches in the fields before the threatened city. The trenches correspond to the furrows and lines which will mark the young man’s forehead as he ages. He is urged not to throw away all his beauty by devoting himself to self-pleasure, but to have children, thus satisfying the world, and Nature, which will keep an account of what he does with his life.

(ஈரேழ் வரிப்பா – 3)

உன்னைப் பார் கண்ணாடியில்

கண்ணாடியில் பார்த்து உன் முகத்திடம் சொல்

இதுதான் தருணம் ! தேவை உனக்கு ஒரு சேய் !

உன்னைப் போலொரு சேயைத் தவிர்த்தால்

உலகுக்குப் புறம்பாய் நடந்து வருவாய்

சேயின் எதிர்காலத் தாய்க் கருவை விலக்குவாய் !

உன்சேய் விழையா ஒரு மாதே இல்லை

சுய சுகத்தில் எவனும் சந்ததி நிறுத்தான் !

அன்னையின் கண்ணாடி நீ ! அதுபோல் நீயும்

தன்னை இளங் குமரியாய்க் காண்பாள்.

உனது சேயைக் காணும் போது

இளமை மீளும் வயதாகும் உனக்கு !

தனித்து செத்தால் அழியும் நின்னெழில் காட்சி !

Sonnets : 3

Look in thy glass, and tell the face thou viewest

Now is the time that face should form another;

Whose fresh repair if now thou not renewest,

Thou dost beguile the world, unbless some mother.

For where is she so fair whose unear’d womb

Disdains the tillage of thy husbandry?

Or who is he so fond will be the tomb

Of his self-love, to stop posterity?

Thou art thy mother’s glass, and she in thee

Calls back the lovely April of her prime:

So thou through windows of thine age shall see

Despite of wrinkles this thy golden time.

But if thou live, remember’d not to be,

Die single, and thine image dies with thee.

Sonnet 3 Summary

The youth is urged once more to look to posterity and to bless the world by begetting children. No woman, however beautiful, would disdain to have him as a mate. Just as he reflects his mother’s beauty, showing how lovely she was in her prime, so a child of his would be a record of his own beauty. In his old age he could look on this child and see an image of what he once was. But if he chooses to remain single, everything will perish with him.

(ஈரேழ் வரிப்பா – 4)

ஏன் வீணாக வேண்டும் ?

உன் பிறப்பெழில் ஏன் வீணாக வேண்டும்

சுய இச்சை உனக்குள் அடங்கிப் போய் ?

இயற்கை தரும்கடன் நேராக எதுவு மில்லை !

எதிர்பார்க்கும் நன்றி தன் இலவசக் கொடைக்கு !

தன்னலமி நீ ஏன் தவறிப் பிழைக்கிறாய் ?

வாரிசாய் வந்த அழகைச் சந்ததிக்கு அளித்திடு !

கடன் பெற்றதைப் பயன் படுத்தல் முறையாம்.

சேமிப்பு பேரளவு ! ஆயினும் வாழாய் நீ !

கைச்சுகப் போக்கு தனிமையில் மட்டுமே !

உன்னை ஏமாற்றிக் கொள்வது நீயே !

என்ன பதிலோ இயற்கை செத்தபின் கேட்டால் ?

ஏற்புடைச் சந்ததி எப்படி விட் டேகுவாய் ?

சந்ததி படைக்கா சுந்தரம் புதைபடும் உன்னுடன் !

விந்தின் பயன் பெறின் பிறவிப் பலன் வாழ்வில் !

Sonnet : 4

Unthrifty loveliness, why dost thou spend

Upon thy self thy beauty’s legacy?

Nature’s bequest gives nothing, but doth lend,

And being frank she lends to those are free:

Then, beauteous niggard, why dost thou abuse

The bounteous largess given thee to give?

Profitless usurer, why dost thou use

So great a sum of sums, yet canst not live?

For having traffic with thy self alone,

Thou of thy self thy sweet self dost deceive:

Then how when nature calls thee to be gone,

What acceptable audit canst thou leave?

Thy unused beauty must be tombed with thee,

Which, used, lives th’ executor to be.

Sonnet 4 Summary

The youth is urged once again not to throw away without regard the beauty which is his to perfection. It is Nature’s gift, but only given on condition that it is used to profit the world, that is, by handing it on to future generations. An analogy is drawn from money-lending: the usurer should use his money wisely. Yet the young man has dealings with himself alone, and cannot give a satisfactory account of time well spent. If he continues to behave in such a way, his beauty will die with him, whereas he could leave inheritors to benefit from his legacy.

(ஈரேழ் வரிப்பா – 5)

பருவத்தின் படைப்பு

உன்னை மென்மையாய் வடித்தவை காலங்கள்

கவர்ச்சி நோக்கில் ஒவ்வொரு விழியும் வசிக்கும் !

கடுமை யாளரும் அநத நோக்கில் விளையாடுவர் !

எழிலைச் சுளுவாய் மீறும் அழகீனப் பண்பு

ஓய்விலாக் காலம் வேனில் நோக்கிச் செல்லும் !

வெறுக்கும் குளிர்காலம் முறிக்கும் வேனிற் பருவம் !

பனிப்படிவு நிறுத்தும் பசுமை இலைக் காட்சி !

எழில்மீது பனிபடரும் ! எங்கும் சூனியப் பொட்டல் !

ஆவியாகும் வேனில் மணம் தடைப்பட வேண்டும்

கொதிவடித் திரவம் கண்ணாடிக் குவளை மிஞ்சும் 1

வனப்பின் விளைவு வனப்போ டிழந்து போகும்

நினைவும் எழிலும் அழிவன எதுவெனத் தெரியா !

ஆயினும் குளிரால் உலரும் மலர்கள் சருகே !

தோற்றம் மறைந்திடும் ! உட்பொருள் இனிக்கும்.

Sonnet : 5

Those hours, that with gentle work did frame

The lovely gaze where every eye doth dwell,

Will play the tyrants to the very same

And that unfair which fairly doth excel:

For never-resting time leads summer on

To hideous winter and confounds him there;

Sap check’d with frost and lusty leaves quite gone,

Beauty o’ersnow’d and bareness every where:

Then, were not summer’s distillation left,

A liquid prisoner pent in walls of glass,

Beauty’s effect with beauty were bereft,

Nor it nor no remembrance what it was:

But flowers distill’d though they with winter meet,

Leese but their show; their substance still lives sweet.

Sonnet 5 Summary

This and the following sonnet are written as a pair.The poet laments the progress of the years, which will play havoc with the young man’s beauty. Human life is like the seasons, spring, summer, autumn’s maturity and fruition, followed by hideous winter. Nothing is left of summer’s beauty except for that which the careful housewife preserves, the essence of roses and other flowers distilled for their perfume. Other than that there is no remembrance of things beautiful. But once distilled, the substance of beauty is always preserved. therefore the youth should consider how his beauty might be best distilled.

(ஈரேழ் வரிப்பா – 6)

பருவத்தின் பிள்ளைகள்

முறிந்த குளிர் காலம் அழிக்க வேண்டாம்

உனது வேனிற் பருவம் சேயாக்கும் முன்பு !

கர்ப்பிணி ஆக்கு ஒருத்தியை பொக்கிசம் ஓரிடத்தில் !

உன் அழகின் அமுது சேய், உன்விந்து வீணாகும் முன்

பணத்தை உவந்து கடன்கொடு வருவாய் பெருக்க !

கடனாளி மகிழ்வான் விழையும் கடன் கிடைத்தால்,

உன்போல் மறு பிரதி பதிப்பது உனக்கது பரிசு !

பத்துச் சேய்கள் பிறந்தால் மெத்தக் களிப்புனக்கு !

ஈரைந்து சிசுக்கள் தங்கின் சந்ததி பெருகும் உன்போல்

மரணம் என் செய்ய முடியும் நீயே மரித்தால்

வருமரபில் உனை வாழ வைத்து விட்டு ?

சுயத் தணிப்புச் சுகம் வேண்டாம், சுந்தரன் நீ

மரணம் வென்றால் புழுக்கள் உனக்குச் சந்ததி !

Sonnet : 6

Then let not winter’s ragged hand deface

In thee thy summer, ere thou be distill’d:

Make sweet some vial; treasure thou some place

With beauty’s treasure, ere it be self-kill’d.

That use is not forbidden usury,

Which happies those that pay the willing loan;

That’s for thyself to breed another thee,

Or ten times happier, be it ten for one;

Ten times thyself were happier than thou art,

If ten of thine ten times refigured thee:

Then what could death do, if thou shouldst depart,

Leaving thee living in posterity?

Be not self-will’d, for thou art much too fair

To be death’s conquest and make worms thine heir.

Summary of Sonnet : 6

Sonnet 6 continues the winter imagery from the previous sonnet and furthers the procreation theme. Winter, symbolizing old age, and summer, symbolizing youth, are diametrically opposed. The theme of the previous sonnet, that summer’s beauty must be distilled and preserved, is here continued. The youth is encouraged to defeat the threatened ravages of winter by having children. Ten children would increase his happiness tenfold, since there would be ten faces to mirror his. Death therefore would be defeated, since he would live for ever through his posterity, even if he should himself die. He is much too beautiful to be merely food for worms, and must be encouraged not to be selfish, but to outwit death and death’s conquering hand.

(ஈரேழ் வரிப்பா – 7)

சேயின்றிப் போனால் !

அதோ ! கிழக்கில் சுடரொளிப் பரிதியின் எழுச்சி

அக்கினித் தலையுடன் ஒவ்வோர் விழிக்குக் கீழும் !

வழிபடுவர் வணங்கி புது வடிவை மனிதர் போல்

விழிநோக்கில் காட்டுவர் தமது புனித மதிப்பை,

சொர்க்க செங்குத்து மலைமேல் ஏறிய பிறகு

வலுத்த இளமை மீளுது மையத்து வயதிலே !

மானிடத் தோற்ற வனப்பு ஒப்பனை செய்யும்

பொன்மயப் பயணம் புரவலன் மேற் கொள்வான் !

உச்சிமேல் ஏறிய தேர் களைப்பில் ஓய்ந்திடும்

வலுவிலா வயதில் ஒளி தேயும் பகல் போல் !

கண்கள் முன்பு கடமை நெறி மாறிப் போயின

இறுதியாய்த் தொடுவானில் சரிந்திடும் சூரியன் !

இளங் காளையே ! வாலிபப் பருவம் விடைபெறும் !

நீயும் நின்வாரிசும் மாயும் ஆண் சேயின்றிப் போயின் !

Sonnet : 7

Lo! in the orient when the gracious light

Lifts up his burning head, each under eye

Doth homage to his new-appearing sight,

Serving with looks his sacred majesty;

And having climb’d the steep-up heavenly hill,

Resembling strong youth in his middle age,

Yet mortal looks adore his beauty still,

Attending on his golden pilgrimage;

But when from highmost pitch, with weary car,

Like feeble age, he reeleth from the day,

The eyes, ‘fore duteous, now converted are

From his low tract and look another way:

So thou, thyself out-going in thy noon,

Unlook’d on diest, unless thou get a son.

Summary of Sonnet : 7

The poet explores another theme, different from those he has pursued in the preceding sonnets. He draws a simile between the rising and setting sun and youth and age. In the sunset of his days the youth will no longer be surrounded by admirers. Unless he has children to carry on the line and reflect his former beauty, he will vanish unknown into the murky depths of time.

When the sun rises, everyone admires it, and pays homage to it, as if it were a king. As it climbs higher in the sky to reach its zenith, mortals admire it still. But as it plunges downwards towards evening, the gaze is averted, and, like ‘unregarded age in corners thrown’, it is ignored and other rising stars take precedence. ‘So you too, fair youth, will be nothing as you age, unless you become the rising sun by having a son.’

(ஈரேழ் வரிப்பா – 8)

செவிக்கினிய இசைபோல் குடும்பம்

செவிக்கினிது கீதம்; இசை கேட்பதில் உனக்கு ஏன் வருத்தம் ?

இனிப்பும் இனிப்பும் தமக்குள் போரிடா ! களிப்பு இன்புறும் களிப்பில்

இசைமேல் இச்சை ஏன், இன்பம் அளிக்கா விட்டால் ?

பூரிப்படை வாயா நீ உனக்குத் துயர் தரும் ஒன்றில் ?

சீரிய இசைச்சுவை இகழும் அவன்தனிக் குடும்ப வாழ்வை,

இல்லற ஐக்கியம் என்றால் நின் செவிப்பறை வெறுக்கும் !

இசையொலி அழிக்கும், பரிவாய் இகழும் உன்னை,

தனிச் சுகத்தில் உடல் உறுப்புகள் தவறாய்ப் பயன்படும்

ஒருநாண் மற்றதின் இனிய கணவன் என்பதைப் நோக்கு

ஒன்றால் ஒன்று அதிர்வது ஒன்றை ஒன்றை உண்டாக்கும்

புனிதக் குடும்பம் போல் பூரிப்புத் தாய்க்குச் சேய் படைப்பு

தாய் தந்தை சேய் இணைப்பு சீரிய கூட்டிசைக் களிப்பு

பற்பல நாண்களின் சீரிசை போல் சதி, பதி சேய் பிணைப்பு

பற்பல நாண்களின் ஊமைக் கீதங்கள் ஒருமைப் படுவது

தனித்து ஒருவனாய்க் கிடப்பதில் நடப்பது ஒன்றில்லை.

Sonnet : 8

Music to hear, why hear’st thou music sadly?

Sweets with sweets war not, joy delights in joy.

Why lovest thou that which thou receivest not gladly,

Or else receivest with pleasure thine annoy?

If the true concord of well-tuned sounds,

By unions married, do offend thine ear,

They do but sweetly chide thee, who confounds

In singleness the parts that thou shouldst bear.

Mark how one string, sweet husband to another,

Strikes each in each by mutual ordering,

Resembling sire and child and happy mother

Who all in one, one pleasing note do sing:

Whose speechless song, being many, seeming one,

Sings this to thee: ‘thou single wilt prove none.’

Sonnet Summary : 8

The theme of the youth’s failure to marry and to have children is continued. A lesson is drawn from his

apparent sadness in listening to music. Music itself is concord and harmony, similar to that which reigns in the happy household of father, child and mother, as if they were separate strings in music which reverberate mutually. The young man is made sad by this harmony because he does not submit to it. In effect it admonishes him, telling him that, in dedicating himself to a single life he makes himself worthless, a nonentity, a nothingness.

(ஈரேழ் வரிப்பா – 9)

ஓர் எச்சரிக்கை

விதவையின் விழி ஈரமாகும் என அஞ்சுவ தற்கா நீ

வீணாக்குவாய் தனக்கிரை யாகுமுன் தனித்துவ வாழ்வை ?

அந்தோ ! நீ சேயின்றி செத்து மறைய நேர்ந்தால்

உலகம் அழுதிடும் உனக்காக விதவை போல் கருதி

ஓயாது அழுதிடும் உலகம் உனது விதவை ஆகும்

ஏனெனில் உன் சந்ததி உனக்குப் பிறகில்லாது போவதால்.

தனித்துள்ள எந்த விதவையும் சிசு பெற்றிட முடியும்

சேய் விழி நோக்கின் அவள் பதி உருவம் தெரியும்

பார் ! வீணாக்கு வோன் பாரில் பாழாக்குவன் அனைத்தும் !

இடம் மாறும் செல்வத்தால், என்றும் வையகம் மகிழும்

தேயும் வாலிப எழில் சேயிலாது, வீணாய் உலக முடிவாய்

பயன் படுத்தாமல் வைத்துப் பாழாக்குவன் பிழை செய்வோன் !

பிறர்மேல் நேசம் நிலைப்ப தில்லை என்றும் உன் நெஞ்சில் !

விந்துகள் அப்படி அழிவதில் வெட்க மில்லை அவனுக்கு !

Sonnet : 9

Is it for fear to wet a widow’s eye

That thou consumest thyself in single life?

Ah! if thou issueless shalt hap to die.

The world will wail thee, like a makeless wife;

The world will be thy widow and still weep

That thou no form of thee hast left behind,

When every private widow well may keep

By children’s eyes her husband’s shape in mind.

Look, what an unthrift in the world doth spend

Shifts but his place, for still the world enjoys it;

But beauty’s waste hath in the world an end,

And kept unused, the user so destroys it.

No love toward others in that bosom sits

That on himself such murderous shame commits.

Sonnet Summary : 9

The poet asks if it is fear of making someone a widow that causes the young man to refuse to marry. The argument is unsound, says the poet, for a beautiful youth must leave behind him a form or copy of himself, otherwise the world itself will endure widowhood, and yet have no consolation for its loss. For it will not be able to view the young man resurrected in the eyes of his children. If he persists in this single obduracy, it is an unforgivable shame, showing lack of love to others and equivalent to murdering himself and all his heirs.

(ஈரேழ் வரிப்பா – 10)

எழில் இனப் பெருக்கம்

ஒரு வேண்டுகோள்

எவள் மீதும் நேசமில்லை என்றுனக்கு வெட்க மில்லை

எதிர்காலச் சந்ததியாய் எது உனக்குப் பிறக்கும் ?

உன்னை நேசிப்போர் பலர். அது உனக்கேற்ற வாதம்

ஆனால் நீ நேசிப்பது யாருமிலை என்பது வெட்ட வெளிச்சம்

எதிர்காலச் சந்ததி இழப்பு உன் கையில் தான் இருக்குது

துயர மில்லை உனக்குப் பரம்பரை இன்றிப் போவதில்

எழில் இல்ல மாளிகை கட்டாமல் அழிப்பதுன் தீர்மானம்

அதைச் செம்மைப் படுத்துவது உன் முக்கிய வேட்கை

அந்தோ ! உன் கருத்தை மாற்று நீ என் தீர்ப்பை மாற்றிட !

நேசத்தை விட்டு வெறுப்பு குடிபுகுதல் நேர்மை ஆகுமா ?

நீயாக இருப்பதில் விருத்தி பரிவு, பணிவு, நளினம் தரட்டும்

உனக்காக மாறிப் பரிவோடு இன விருத்தி நிரூபணம் செய்

உன் சந்ததியாய் ஒன்றை உருவாக்கு என் மீதுள்ள நேசத்தால்

இளமை எழில் நித்தியச் சந்ததியாய் நிலவிப் பெருகட்டும்.

Sonnet : 10

For shame deny that thou bear’st love to any,

Who for thy self art so unprovident.

Grant, if thou wilt, thou art beloved of many,

But that thou none lov’st is most evident:

For thou art so possessed with murderous hate,

That ‘gainst thy self thou stick’st not to conspire,

Seeking that beauteous roof to ruinate

Which to repair should be thy chief desire.

O! change thy thought, that I may change my mind:

Shall hate be fairer lodged than gentle love?

Be, as thy presence is, gracious and kind,

Or to thyself at least kind-hearted prove:

Make thee another self for love of me,

That beauty still may live in thine or thee.

Sonnet Summary : 10

This is the first sonnet of the series in which the poet declares a personal interest in the youth, rather than the general one of desiring for the world’s sake that it be not deprived of his progeny. Here there are two statements, firstly, that he wishes to have an opportunity to change his opinion of the youth (l.9), as implying that his (the poet’s) better opinion is of some value; secondly he attempts the persuasive argument of ‘for love of me’ in order to produce a change in the youth’s intentions. Neither of these amount to a declaration of love, although they do half imply it, for what is love if it is not reciprocated? In any case it is in some sense preparatory to the more impassioned statements of several of the sonnets which are to follow.

Apart from that, the argument of this sonnet is similar to that of the previous one: ‘Be not wilfully selfish and cruel to mankind, but replace and repair your decaying mansion by procreation. In that way you live on, and I myself and others will think the better of you.’

Information :

1. Shakespeare’s Sonnets Edited By: Stanley Wells (1985)

2. http://www.william-shakespeare.info/william-shakespeare-sonnets.htm (Sonnets Text)

3. http://www.sparknotes.com/shakespeare/shakesonnets/section2.rhtml (Spark Notes to Sonnets)

4. http://www.gradesaver.com/shakespeares-sonnets/study-guide/ (Sonnets Study Guide)

5. http://www.gradesaver.com/shakespeares-sonnets/study-guide/short-summary/ (Sonnets summary)

6. The Sonnets of William Shakespeare By :Lomboll House (1987)

S. Jayabarathan (இந்த மின்-அஞ்சல் முகவரி spambots இடமிருந்து பாதுகாக்கப்படுகிறது. இதைப் பார்ப்பதற்குத் தாங்கள் JavaScript-ஐ இயலுமைப்படுத்த வேண்டும்.)

பதிவுகள். காம் மின்னூல் தொகுப்புகள்

பதிவுகள். காம் மின்னூல் தொகுப்புகள்